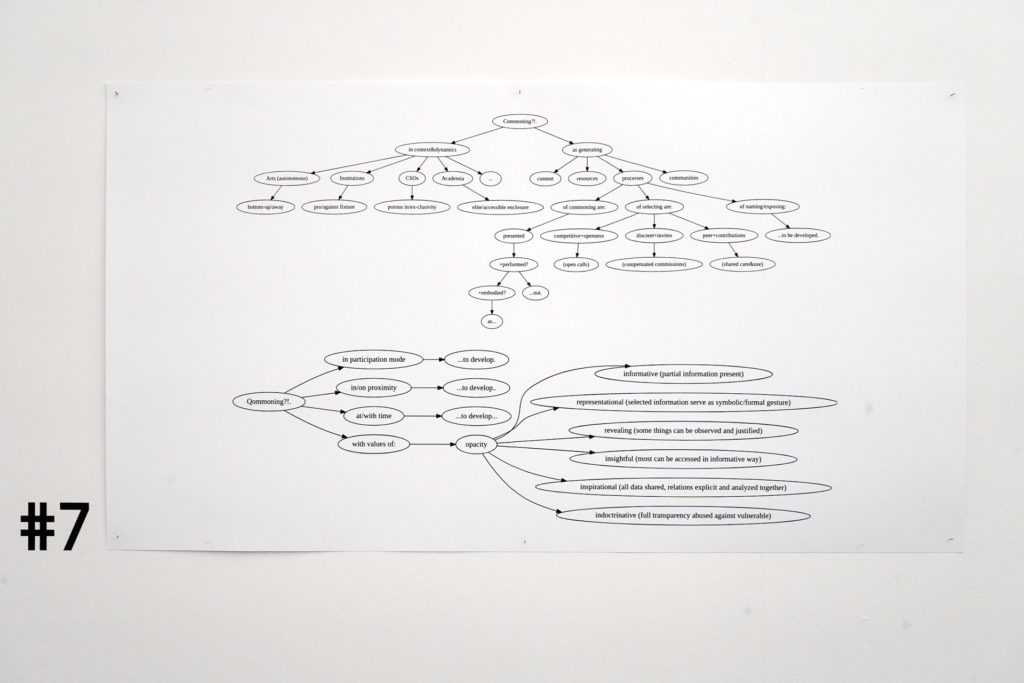

This is an edited version of a presentation given at the “TCS Philosophy & Literature Conference 2019” (29 May – 2 June 2019) as part of a panel called “Creating Commons”, with Jeremy Gilbert and Tiziana Terranova. At this panel, my task was to present our research project. Given the short time for the presentation (20 minutes), I focused on four library projects, Ubu, aaaaarg, Monoskop, and Memory of the World (MotW) and I tried to distill some of the things we learned through them into “four theses on cultural commons”. So, here they are:

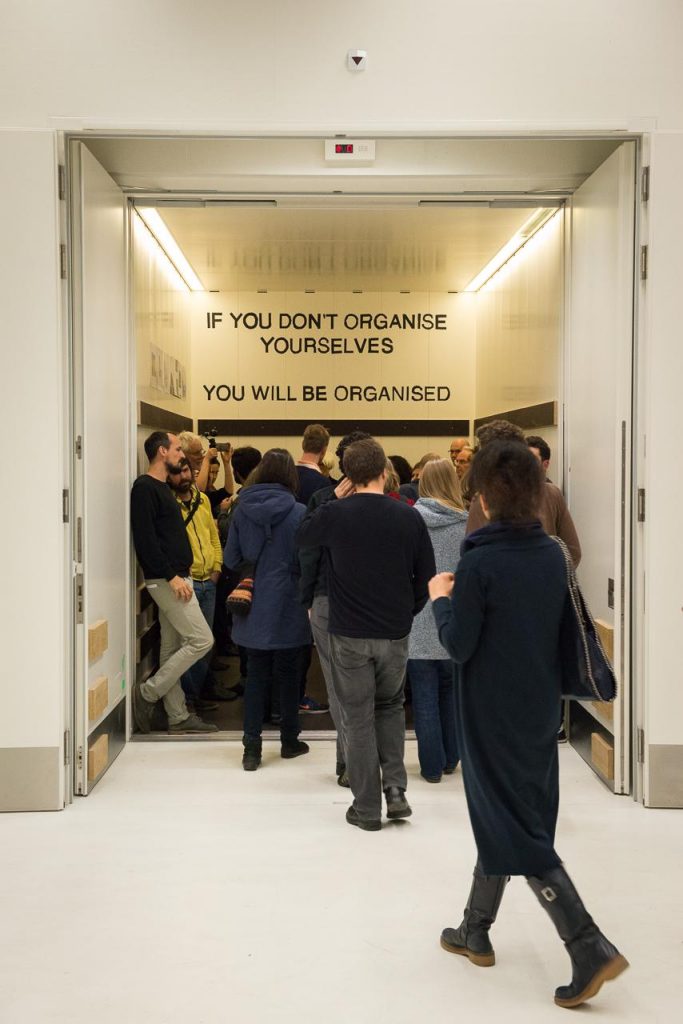

1. Infrastructure is politics

In some way, this is obvious but bears repeating. Infrastructure is politics. The more one controls the infrastructure, the more one can shape it to support whatever one wants to do through it. The less one does, the more one is at the mercy of whoever does control it. Of course, “control” over infrastructure is not a one-sided imposition of the will, but also brings with it its own sets of dependencies, responsibilities, and constraints. There is always a deep entanglement with infrastructure, and the way is entanglement is shaped is part of the politics of the projects.

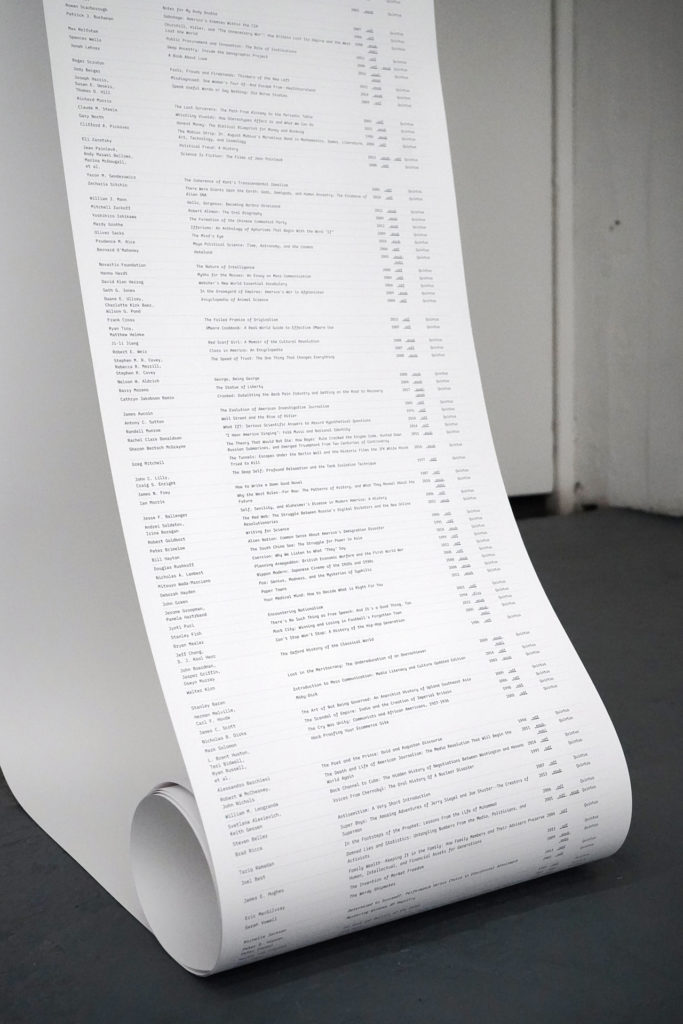

In the case of the four projects, infrastructure that is directly under their own control comprises server hardware and all the software that runs on top of it.

This does not mean that one has to become a technical expert. Ubu, for example, is technically primitive, simple HTML, no change since 1996, coded by hand by Kenneth Goldsmith, using standard, simple tools such as BBedit (a text editor) and an FTP (file transfer protocol) application to send the locally edited files to the server and thus make them available on the internet. Anyone can learn the necessary technical skills in a single afternoon. Monoskop is technically a bit more sophisticated (but still using standard, open source software packages) whereas aaaaarg and MotW run more complex, custom-built software.

The point, however, is not the sophistication, but the ability to implement one’s own interests and desires. To set the rules of engagement. And this is not even necessarily a technological question. For example, both Ubu and Monoskop when getting a legal complaint (for example, in the form a ‘cease and desist’ letter) try first to engage with the sender, getting him/her to understand the character and motives of the project and trying to convince him/her that it’s actually in his/her interest to have the work on the site. Such an exchange can take some time but is successful quite often. Only if no agreement can be found, a work is removed from the site at the author/owners request. But the control over the infrastructure, and not be subject to some automated process, is a pre-condition to be able to start this conversation in the first place.

Yet, the Internet is a complex medium, consisting of many different layers, and it’s impossible to control all of them. For example, the domain name system is more centrally administrated and control over one own domain name rests, ultimately, with the registrar. aaaaarg, for example, had to change its domain name several times, after it lost access to them through their registrars willingness to react to complaints. So, control and autonomy in technical systems are always limited, but this makes it even more necessary to think carefully about the politics of infrastructure.

2. Copyright is so broken that few are left to enforce it

The copyright system is broken, in more than one way. And there have been many attempts to fix it, some aiming to expand it to new domains and strengthen enforcement, while others introduced new licenses that make sharing and transformation easier. While the former might, in the medium turn, pose new challenges for the four projects, the latter is not relevant because they all work with existing materials that cannot be re-released under a free license.

Yet, all of these projects, despite massive, unauthorized use of copyrighted material exist with relatively little interference from copyright owners. So, one can see that outside hyper-commercial commodity culture, there is a vast grey zone where people and companies are neither really able nor terribly interested in enforcing copyright.

In part, this is the shadow world of orphaned works, works where the formal copyright owner (or his or her successors) have lost all interest in works, yet they have never been released into the public domain. The other part of the grey zone is comprised of authors and owners who are no longer interested in exclusivity that copyright confers them. Rather than clinging to the non-performing economic model of copyright, they operate under a different logic, being happy to see their works being added to a context where they can be accessed, understood and develop old and new meanings. All projects have received donations from authors and copyright holders, eager to have their works included in the collections and contexts created by them.

This is made possible because also the projects themselves do not operate under commercial logic of copyright and legal formalities of licenses but under a different set of rules which are appealing also to authors and (nominal) right holders.

3. Care is core

Care here is used in a broad sense that does include care towards things and care towards people. As such, it is about entanglement, about ways of being related and dependent, and such ways are always ambiguous and can be contentious.

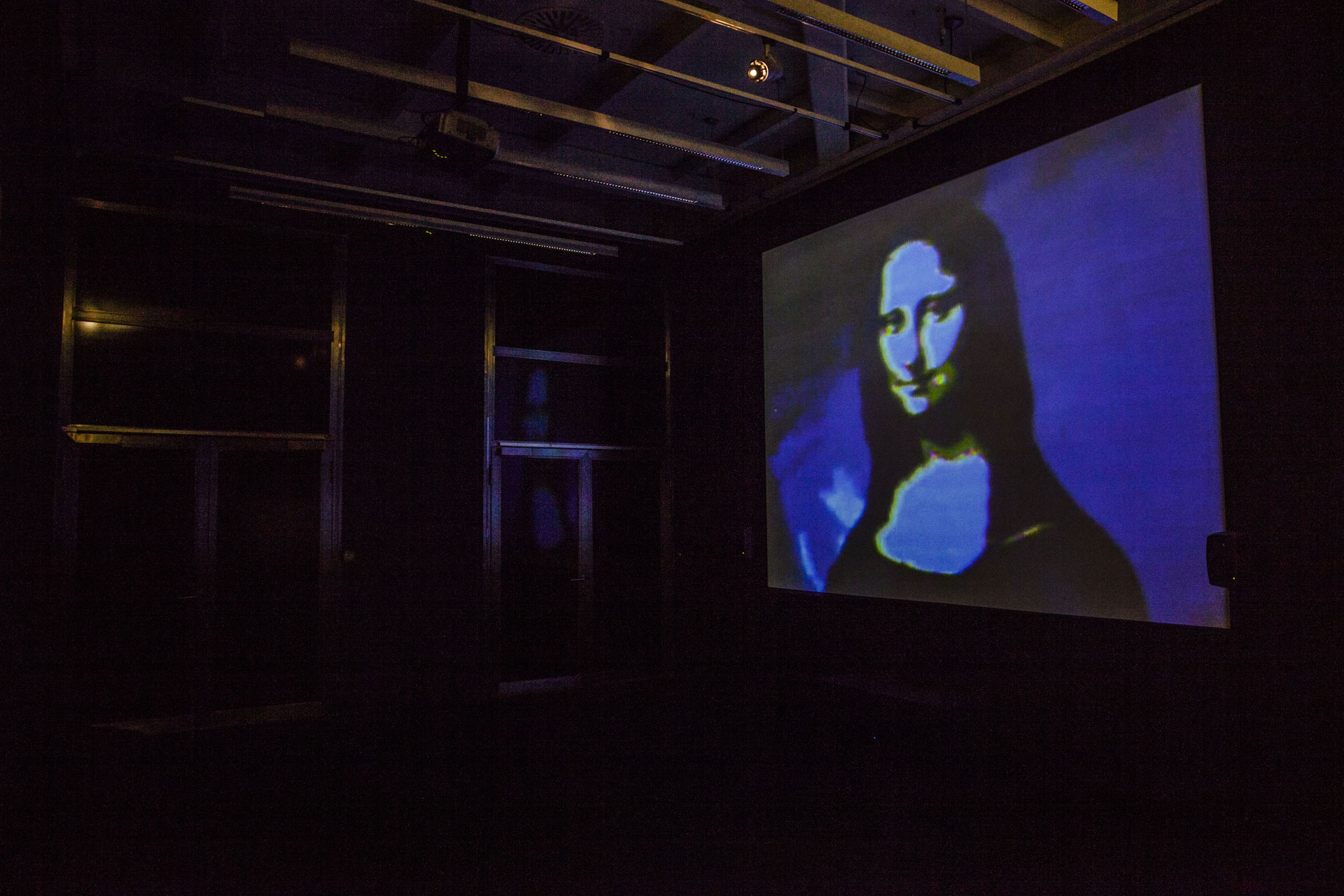

Care, in the context of these projects, allows to think about, and enact, a relationship towards things that does not involve the notions of property and exclusivity (which are in crisis in the digital domain anyway). And by establishing such a relations to things, it is also possible to establish different sets of relationships to people.

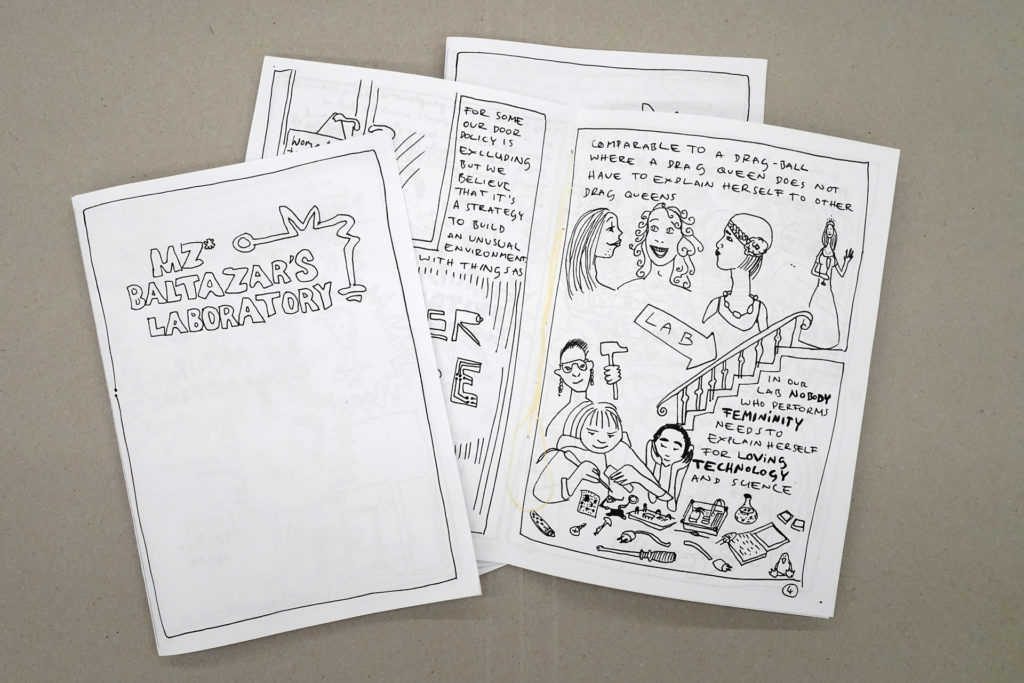

The projects use different terms to describe what it is that they are doing. Several use the term curation, which of course is directly derived from the Latin word “curare,” to care. They are for the work by providing a context for them in which they can unfold already known and previously unknown meanings, create new types of use-value in the absence of exchange-value.

MOfW used the term Custodianship derived the Latin “custodia,” meaning protection or safekeeping.

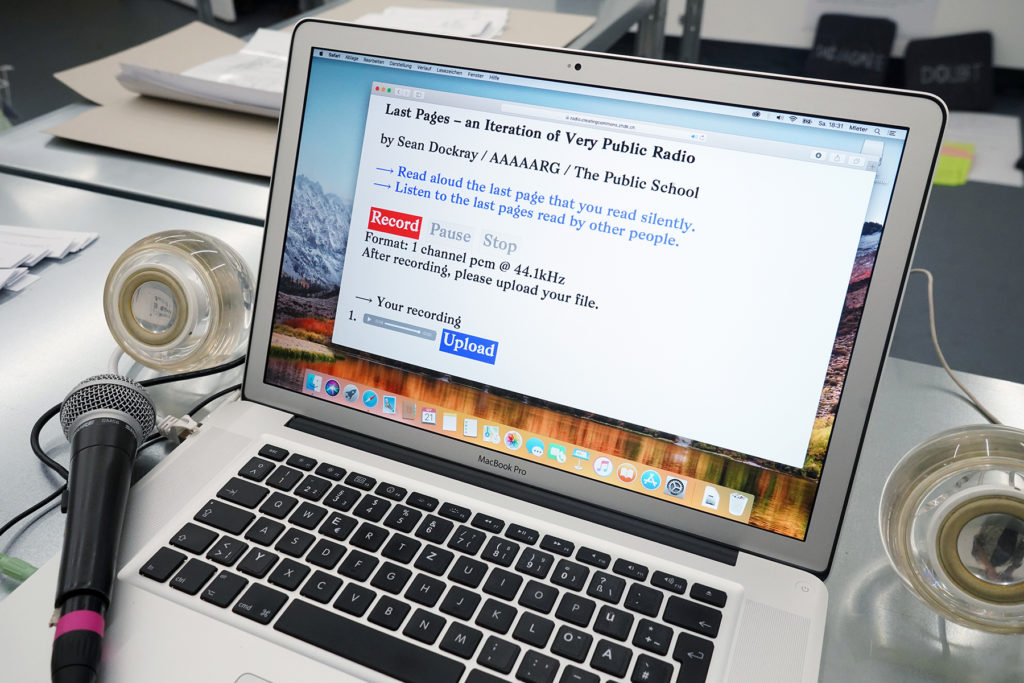

People thus can relate differently to the works and each other. aaaaarg, for example, aims to foster a practice of “reading together.” This is about turning what is normally a solitary practice, reading, into a communal one, forging a microcontext in which an idea can resonate, grow and be transformed to the particular interest and situatedness of the reading group

But establishing relations of care can be contientious, because it challenges notions of property, which are not only commercial, but also have a subjective dimension, for example, when artists and authors see their work as a direct expression of their individuality and thus want to exercise author control. Law suits can ensue which pit these two types of relations against each other.

More interesting is are the ambiguous elements of care, because it generates dependencies or forms of entanglements that may not be easy to loosen. All archives and libraries mentioned here have been sliding, in some way or another, from being artistic projects to becoming infrastructures and institutions other people depend on. So the artists who started be project and who take their responsibility towards the community of users seriously, find that they cannot leave anymore without doing damage to a set of relationships they care about.

This is in stark contrast to property relations, where the exclusive control allows also to discharge all responsibilities over a thing, either be selling it, or be simply ending one care for it.

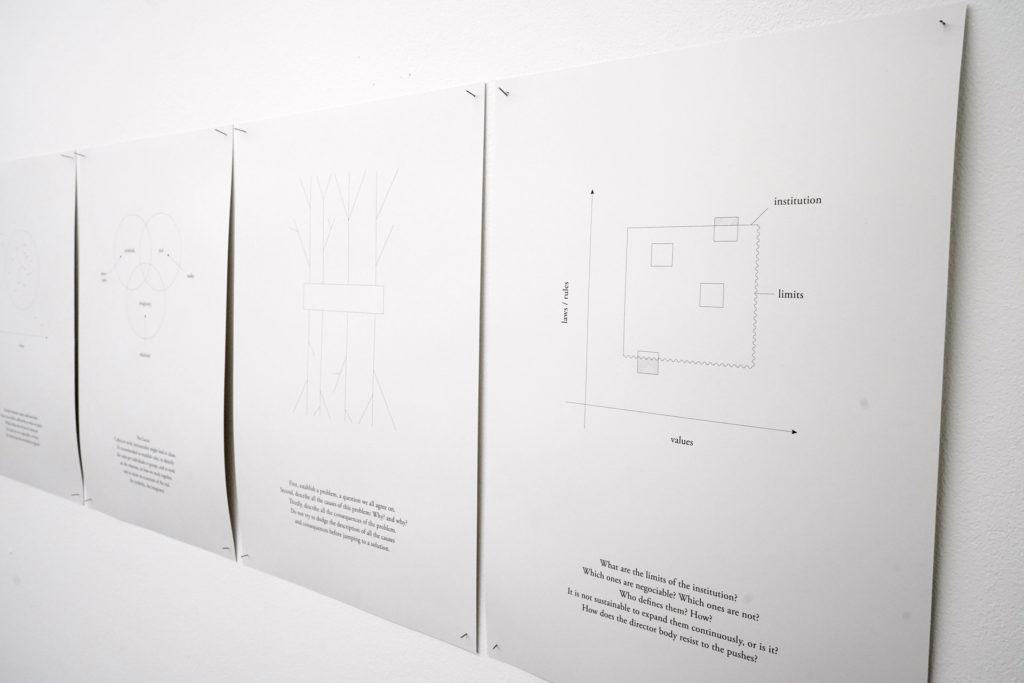

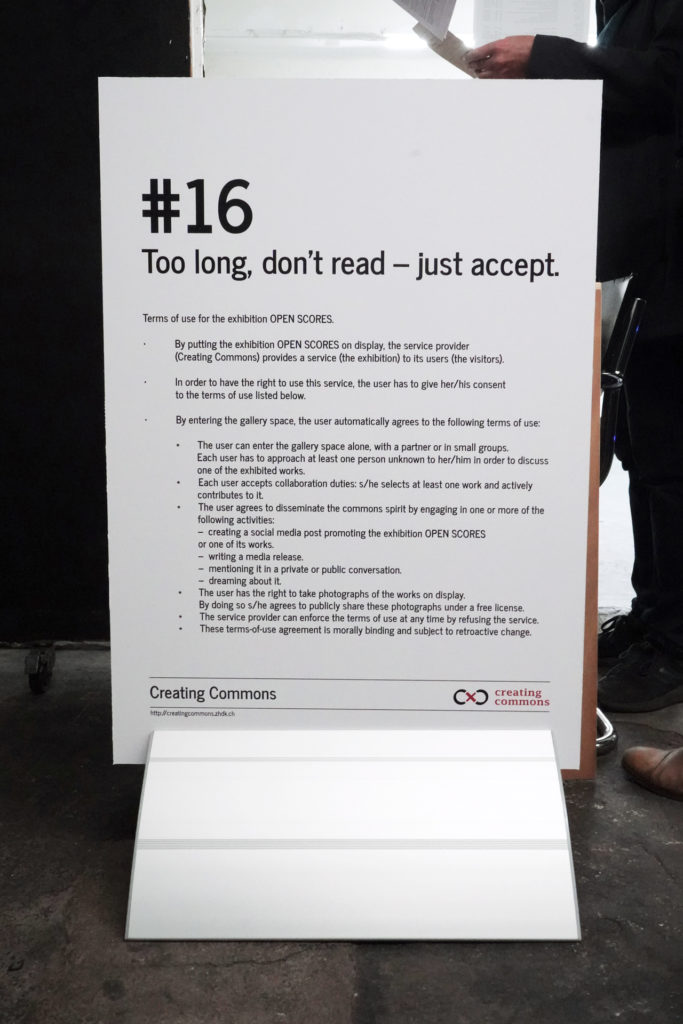

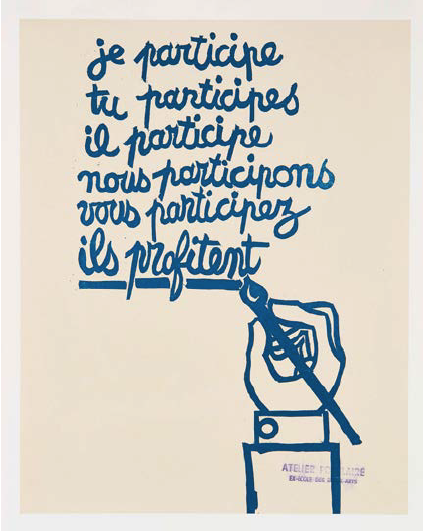

4. Appropriation is better than participation

Part of the context of many of these projects are practices of socially-engaged art, which, during the 1990s, put great emphasis on various forms of participation. Audiences were no longer regarded as passive consumers of finished artworks, but as active “participants” involved in giving shape to the work, in its material form and/or process. During the 2000, under the framework of neo-liberal art institutions, this all-too-often morphed into a kind of top-down activation, where people are tasked to interpret and fill-out roles, without ever being able to challenge the basic framework under which they were tasked to act.

So, none of the projects uses the term participation. At the core of the projects, there is collaboration, that is dense and long-term forms of working together and also includes thinking about, and setting, the modes, goals, and directions of the collaboration itself.

Projects are more about creating conditions in which the material they provide can be appropriated within, but crucially, also outside the framework provided to the artist or the project itself. Users of the free resource are free and encouraged to find their own uses for the material. In this sense, the aim of these projects is not so much about handing out roles to people within a predefined game but allowing them to define their own game.

For example, Kenneth Goldsmith’s artistic practice that led him to create and maintain Ubu, revolves around the notion of “uncreativity”, meaning it’s less important to create something new (there is already an abundance of everything), but provide context for existing material in which it can be assessed in different ways. But it’s not necessary to be particularly interested in, or even having to subscribe to this idea of the role of the artists in the digital domain, for Ubu to be a useful resource and to be able to take material and import it into whatever context and form of use one deems worthy of one’s time.

In a digital context, where every division is a multiplication (at least in terms of data) and in the absence of enforced copyright restriction to multiplication, this is relatively easy to do.

Beyond the immediate context of these projects, I think this shift from participation to appropriation points more generally to a transformation of political subjectivity and organization, and the need to construct collectives that encompass a multiplicity of frames, rather than establish a single one.